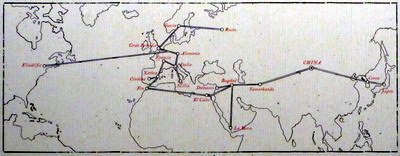

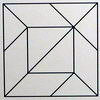

The invention of paper is dated in the 2nd century, in China. Paper crossed Samarkand path to Occident, at the last days of 8th century, where it was spreaded between the ninth and 15th century. There is no knowledge about paper folding in China but the Dunhuang Manuscripts. There is also no information about the regions where paper arrived. It seems that paper folding evolution happened parallelly in Orient and Occident without any contact or influence between them. The oldest data shows a pattern with cuts (jewellery box) in Occident and without them in Orient (noshi). Both models are included in the packaging modelling. Experts tried to systematize the peculiarities and deferences of both traditions in terms of folding tendencies and use of models. In occidental origami, the use of foldings with 45° dominated in models, whereas 22.5° did in oriental origami. In Orient, the use of cuts was, frequently, part of the foundation of the models. Some experts suggest that it could happen because the resistance of paper to be ripped was higher in Orient, so it was easier to make soft unions with less and more resistant paper bridges. In Occident, cutting was't part of the foundation of the models. Some hypothesis specify that this could be because the origin of paper folding was born from napkin folding. In late 19th century, both traditions met and since then influences are reciprocal. From the 90s, the expansion of Internet thanks to globalization and the easy access to communications and its instantaneously, triggered the next quality advance in the origami evolution.

Oriental

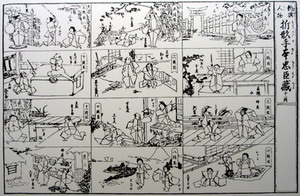

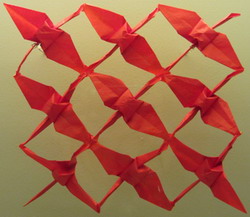

The invention of paper is officially given to Cai Lun in 105 a.D. in China, but it is possible that the technique principle was defined between 247-195 b.C. In the 7th century, fabrication of paper arrives to Korea and Japan. In spite of being known Dunhuang manuscripts (907-960) in China, which show some kind of sheets folded to make little notebooks and books, there is no documentation about any specific model. There is also no documentation about any model in Korea. Schools of etiquette in the Muromachi period, in Japan (14th-16th century), were based on Chinese's. The school of etiquette Ogasawara counted with ceremonial and protocolary foldings. Some of these foldings were used as wrappers, including those with a Shintoism relation, giving the same worth to the content as the context. Japan kept trade relationships with Occident from 1543 until 1639, when it was limited to Holland and China. It would remain closed to the rest of the world until 1868. There is no information about exchange of folding models during the years of commercial period but, maybe, the Chinese junk. The first documented model in Japan is from early 18th century (crane, Japanese emblematic model; little boat...). Late this century, the book Hiden Sembazuru Orikata appeared. It shows a base sheet with cuttings to make thousands of models of cranes of different sizes joined by slight paper connections. In the middle of 19th century, the book nowadays known with the title Kan-no-mado appears. It shows models and developments created with great skills and beauty, most of them with cuttings. In oriental tradition, cuts have been always integrated (kirigami). From 1868, when Japan opened its borderlines to the rest of the world, influences flowed in both ways.

|

105 a.C.

Cai Lun. Traditionally known as the inventor of paper in China.

|

|

|

|

14th century

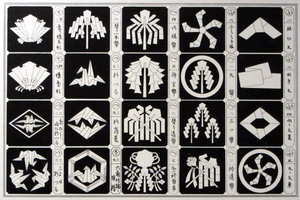

Ocho and Mecho Ceremony.

Osagawara School of Etiquette.

"(After the bride, the groom and the relatives join and sit down)... Then, two married women take a bottle of wine each one... and they put them in the lowest part of the room... One bottle has a male butterfly made of paper tied on it, the other one a female paper butterfly... (and the wine of the two bottles is served in the vessel)... The emptying of both bottles at the same time, the night of the wedding, represents the union that is being done."

|

|

1519

When Hernán Cortés arrives to Tenochtitlán, Aztec and Maya books made of amate paper already existed. These books, whose texture was like pasteboard, were folded like an accordion.

|

|

1734

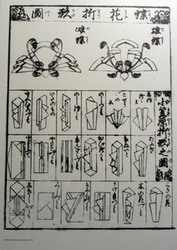

The Japanese book Ram-ma Zushiki shows illustrations of folded models.

|

|

|

|

|

1845

Kan no mado (A window for cold weather) is a section of the fifty little volumes compilation (Kayaragusa), copied by Kazuyuki Adachi, which includes the development of forty-nine model of recreational and ceremonial origami.

|

|

|

|

1955

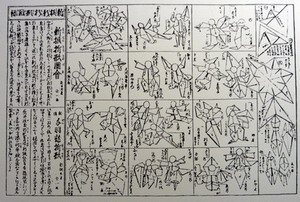

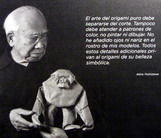

Akira Yoshizawa published in 1955 his first book Atarashi Origami Geijutsu (New Art of Origami), in which he defends the origami without cuts and he presents, for first time, the diagrams to use from this moment in all the world.

|

Occidental

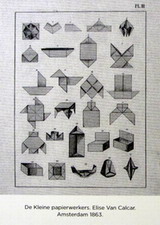

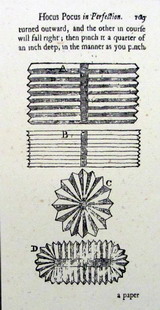

Both, papyrus and parchment, were folded for an utilitarian end (shipment of documents, maps...) Paper arrives to Islam, in the 8th century, through Samarkand and is there where its usage expands to Baghdad, Asia Minor, North of Africa, Spain and the rest of Europe. Its popularity grew so fast that, in 1035, many objects were wrapped with paper in Egyptian bazaars and in Fez (Morocco), in 1200, the number of working paper mills ascended to four hundred. Utilitarian foldings (wrappers, little drugstore bags, medicinal plants conservation, boxes, moulds for sweets...) were the most used in the beginning of the history of paper. These foldings could be used some time before with parchment. In Occident, simbolic folding is almost non-existent, with the exception of the hypothetical folding in the astrological square or the message cards of 19th century. Folding as leisure and/or artistic, starts in the 17th century. Maybe because it was an economic way of study, practise and education of napkin folding exhibited in aristocratic tables in the last times of XVI and XVII centuries. The first documented foldings as hobby with accordion base or multiform, the same used in napkin folding, support this origin. This textil origin could explain the idea of no cuts in occidental origami. The first documentation of origami models in Occident is from early 18th century. The book Hocus Pocus improved or Sports and Pastimes shows a multiform folding to make some models without cutting the paper. There is only one clue that could explain the possible transmission of origami knowledge, between Japan and Europe, before 1868. One illustration from a Dutch book, from 1806, shows for the first time in Occident the Chinese junk. In this period, Japan only had commercial relationships with Holland. From 1868, when Japan opened its borderlines to the rest of the world, influences flowed in both ways.

|

4th century

Liturgical fans or flycatcher. Liturgical item derived from profane fan, used to cover from the sun, refresh and drive insects away.

|

|

|

1056

First reference of a paper mill in Xátiva (Valencia). In the 12th century, the geographer Al-Idrisi wrote about Xátiva: "A paper of the best quality in the world is produced and it is well known in Orient and Occident".

|

|

|

12th century

The notebook, in which the medieval manuscripts were divided, were made with several sheets (8, 10, 12, 16, 24). Combined foldings made that the internal and external sides of the parchment were perfectly faced. Some documents are conserved, with up to eight pages on each side.

|

|

|

1532

Georg Gisze holds in his hands a letter folded, which remains closed by putting part of the paper inside of a backside flap.

|

|

|

1572

During a feast celebrated by Pope Gregory XIII, the table is set with folded napkins and a castle made with the same technique in the middle.

Geigher published Li tre trattati (1629) with the chapter Trattato delle piegature dedicated to the folding of napkins. He teaches this technique in the University of Padova, using paper firstly.

|

|

|

1710

For the first time, the trouble-wit fold in accordion or multiform appears in the book Hocus Pocus Improved or Sportsand Pastimes, for various models.

|

|

|

17th century

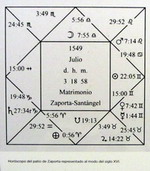

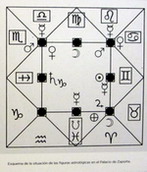

In Central Europe, baptism certificates were folded following a template that reminds the lines of an astrology card or the foldings of a pajarita.

|

|

|

|

|

1806

Among Marie Laetitia's toys, we can find a "capuchino" made with a playing card and a bird.

|

|

|

1806

Chinese junk (or king and queen's boat or gondola) appears for the first time in Occident in a picture in a Dutch book. Hollanders were the only European people who had trade relationships with Japan.

|

|

|

1850

Friedrich Fröbel, kindergarten founder (a scholastic system for infants or children based on games), published notes about the use of origami in the education.

|

|

|

1885

The flapping bird, radically different from the traditional Japanese crane, appears on documents for the first time in La Nature, in 1885.

In some of the Universal Expositions that began in 1855, the Japanese pavilion showed folding paper figures (frog, bird, samurai hat, parrot...).

|

|

|

1902

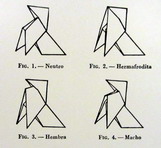

Miguel de Unamuno (1864-1936)

First edition of Love and pedagogy, which includes the ironic manuscript Apuntes para un tratado de cocotología after the epilogue.

"The pajarita is, with no doubt, the architectonic form, we can say, that paper wants and requires; the shape that the perfection of a paper figure comes from, the perfect origami being... And we dare to suspect that children have born for the pajarita and no this one for them..."

|

|

|

1927

In the Bauhaus, German school of craft, design, art y architecture founded in 1919 by Walter Gropius, the teacher Josef Albers uses origami as design element base. Albers escaped to United States where he kept using origami in his classes.

|

|

|

1929

In a park of Huesca, the sculpture Las pajaritas is risen up. Ramón Acín's work, the first sculpture in the world dedicated to a paper figure.

|

|

|

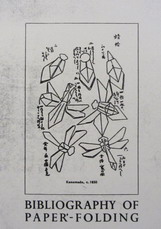

1952

First origami biographic compilation made by G. Legman. It includes one hundred and sixty references.

|

|

|

1952

First periodical meetings of Peña papiroflexista, finally named Grupo Zaragozano de Papiroflexia, whose members will meet without interruption until the present, but the period between 1972 and 1978.

Their view of origami as and art and a science demands "orthodoxy" (no cuts).

|

|