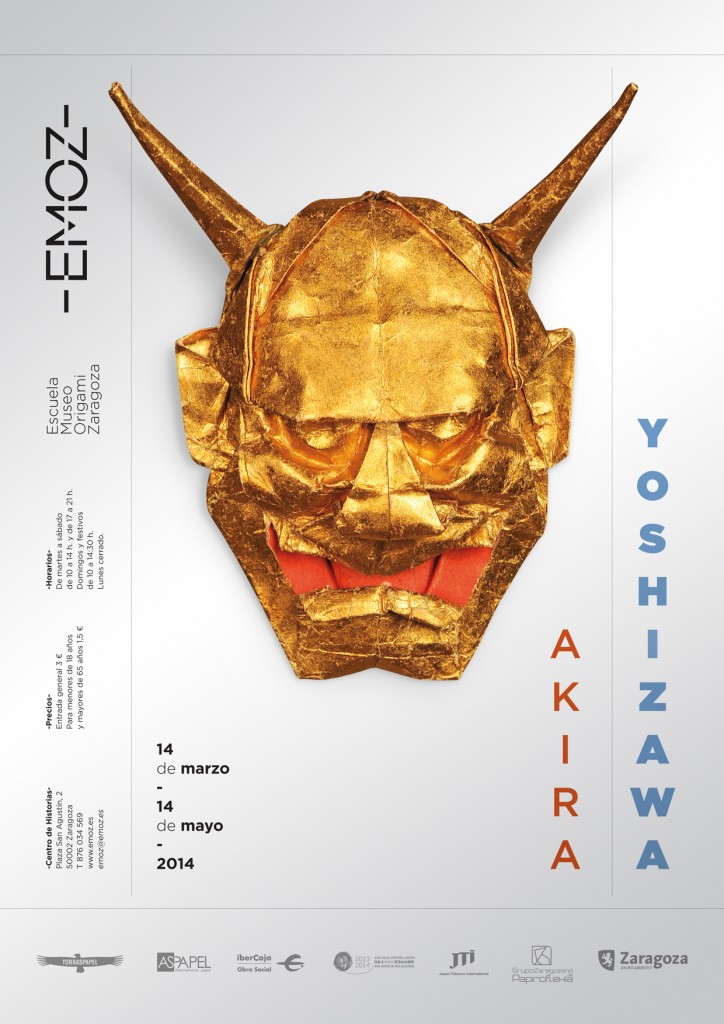

Akira Yoshizawa is well known by every artist of the paper folding as the grandmaster who revolutionized and transformed the origami into a creative and artistic activity.

Himself and his biography tell the history of an artist who gave his life to a “mision”.

Yoshizawa is not only a creator of new models, that is object of admiration, but he endow the origami with a complex and polyhedral context. Philosophy, transcendence, respect to the artistic tradition, love to the paper, biology, science, education, art and creation are all together in his models. His birth place, Japan, is not less important in this combination.

1911

Born the 14th of March in Kaminokawa, prefecture of Tochigi (Tochigi-Ken) not far from Tokyo (Japan), in a farmer family.

1915

Yoshizawa starts to be interested in origami when a neighbour gifted an origami figure, to his ill mother, made from a newspaper sheet.

1924

Starts to work in a foundry (or heavy machine factory) as apprentice (or steel blacksmith) and finally he will teach, to the new employees, basic geometry required for the work and for that end he will use origami.

1935

Leaves the foundry and studies for two years to become a buddhist monk. In spite of didn’t get into a monastery, he would always be a devoted man.

1937

Leaves his monk studies for monk and decides to spend full time on origami.

Lives in poor conditions for almost fifteen years selling tsukudani (little fishes cooked in soy sauce) from door to door.

1938

Marries with his first wife, who will die close to the end of the World War I.

1950

From a little exhibition in Utsunomiya Education Hall, in connexion with an educational congress, the Toshigi district Teacher’s Association recognizes Yoshizawa’s work as creative and educational art.

1952

Asahi Graph, a magazine specialized in big photograph productions, asks him to reproduce the twelve animals of the oriental zodiac in origami, for the edition of January, 1952.

As it is related, the publisher Tadasu Iizawa finds Yoshizawa wearing an old military suit and commands to accommodate him in a hotel until the end of the job.

Great repercussion of the article in Japan (is one of the ways that Legman finally meets Yoshizawa).

1953

Gershon Legman (1917-1999) dedicated part of his life studying the tendencies and history of origami (the first origami historian) and made the first international origami bibliographic list, Bibliography of Paperfolding.

In 1952 he get the book Origami to Kirinuki by Saburo Ueda (1951 edition) in which it is shown the folding of a peacock, whose creases reminds Legman the Spanish pajaritas. He writes to the author with the hypothesis that maybe Japanese origami, after the trade routes opening, has received influences from Spanish school and names Miguel de Unamuno. Ueda gives the letter to the Fujin Koron (the most popular women magazine in Japan) publisher, Masamichi Takarada. Takarada writes back to Legman, introducing him to Yoshizawa. “Besides studying traditional origami, Yoshizawa has developed more than one thousand new designs”. Takarada asks Yoshizawa to write Legman.

Legman finds the copy called Kan-no-mado of an origami Japanese classic in the Library of Congress and writes to Yoshizawa asking him for the original.

After so much searching (in the after war period nobody has enough time for origami, Akira says) Yoshizawa finally finds the copies of Kayaragusa, known with the name Kan-no-mado, written by Kazayuki Adachi, for the Asahi Newspaper, in Osaka.

Yoshizawa writes Legman and he sends him three models: a camel, a peacock and a little chicken.

1954

Founded the Kokusai Origami Kenkyu-kai (The International Origami Centre) in Tokyo.

Publishes his first book Adarasi Origami Geijutsu (Origami Art). It is the first book that uses the system of diagrams and symbols.

1955

Legman administrates a possible exhibition with Yoshizawa’s models in Paris. In June, Yoshizawa sends some models (153 counted by Legman, 300 in words of Yoshizawa). The exhibition in Paris can’t be done, at last.

With the models received, they set an exhibition in Stedjelik Museum, in the city of Amsterdam (Holland).

Along the time of the exhibition, Legman teaches daily origami classes.

The Japanese ambassador in Holland, Suemasa Okamoto, writes to Yoshizawa sending him news about the great repercussion of his exhibition and tells him that the European feelings to Japan aren’t good and his exhibition is improving the relationship between Holland and Japan. “This thrilled me so deeply”.

It was pretending to take the exhibition to other places, but none prospered.

1956

Publishes Origami Tokuhon (Origami Reader).

Marries with Kiyo, his second wife.

1957

Publishes Origami Dokuhon.

1959

Legman sends to Lillian Oppenheimer, for the Nueva York Coopers Union Museum exhibition, part of the creations received from Yoshizawa. There, Miguel de Unamuno’s work (table, raven, teapot, elephant and frog) is shown too.

Some of Yoshizawa’s models are in Legman’s hands. After Legman death, his family donates them to the British Origami Society. After close to fifty years, Kiyo, wife of Yoshizawa, watches the photograph of the owl (or barn owl) sent to Amsterdam in a title page of the BOS from 2003. That is when the recovering of “lost” models starts. Dave Brill takes pictures of them and then sends them back to Yoshizawa.

Ends the developing of the cicada after twenty-three years of tries.

1963

His book, Tanoshii Origami (Joyful Origami), wins the cultural prize Mainnichi Shuppan.

1965

Strats visits to other countries, promoted by the Ministry of External Affairs of Japan, through the Japan Foundation.

In these missions he will travel to more than fifty countries.

1968

Yoshizawa’s work is shown in a exhibition in Colegio Mayor Universitario Cerbuna, in Zaragoza. Eduardo Galvez, from Grupo Zaragozano, appreciates to Yoshizawa his collaboration and sends him ten models of the GZ.

1970

Exhibition “The land of fairy tales” in Yokohama (Japan).

“Beacon Magazine of Hawai” publishes a Leland Stowe’s article, extracted later in Selections from Reader´s Digest and appeared y apareciÓ in thirteen editions around all the world. In Spanish in November, in 1970, under the title “Origami, magia en papel”.

1981

Sends models for the exhibition “Tribute to the Grupo Zaragozano 40-70”, developed in Zaragoza.

1983

The Japanese Emperor, Hiroito, gives him The Order of the Rising Sun, one of the highest honours that a Japanese citizen can receive.

1989

The work of Yoshizawa is estimated in 50.000 creations. Only few hundreds of them were published in his eighteen books.

1989

Collaborates in the development of his models in the magazine Toshiba Medical Review. These creations will appear in the title page.

1992

The Japanese pavilion in the Expo of Sevilla presents the exhibition Four seasons in Japan.

Visits Madrid in June.

Visits Zaragoza and the Grupo Zaragozano de Papiroflexia in July (he will come back again in 1997).

1997

Visits Zaragoza (so does Momotani, Brill, Leonardi, Takao, Inoue…) (his last coming was in 1992).

1998

Is invited to exhibit his figures in the Louvre Museum, with other artists, in the highest origami exhibition ever done.

1999

Invites Carlos Pomarón, important member of Grupo Zaragozano de Papiroflexia, to the Tribute Exhibition, celebrated in Japan in his 88th birthday.

2003

In the number of Augusts of the BOS the picture of Yoshizawa’s owl or barn owl is shown. So it does, in the next number, the picture of his self portrait that was sent to the exhibition of Amsterdam. There is when the recovering of fifty “lost” models, sent to Legmanin in 1953, starts.

2005 Dies the 14th of March.

2012

The 14th of March Google Co. pays him tribute with a commemorative doodle created by Robert Lang.